Photo © Stephen Mark Sullivan

By Barry Santini

In the world of consumer precision optics, which includes cameras, telescopes and binoculars, few people would trade optical performance for better cosmetics. Yet every day, in almost any optical office around the country, someone is making decisions that prioritize an eyeglass’ cosmetic appearance rather than good optics. This process actually begins when opticians try to help choose the “proper” frame style for the patient’s prescription. This often is in conflict with the fashion desires of the buyer, resulting in scenarios where the sheer want of the wearer trumps all other considerations. Now, both lab and optician have to figure out how to make it work. Sometimes even skilled opticians will write eyeglass orders without full knowledge of the impact their choices will have on the acuity, comfort, visual utility or personal preferences of the wearer.

Looking back at eyewear’s glorious 700-year tradition delivering only optical excellence, it’s interesting to speculate exactly how, why and when did opticians arrive at the juncture where cosmetics began to count more than optics in configuring a pair of glasses? Today, as Rx eyewear becomes impacted by the exponential growth of freeform surfacing and high precision lens making, it’s an opportune time to consider if we are truly using all the high-tech tools at our disposal to strike the optimal balance between optics and cosmetics. Even if we consider the refinement obtainable in precision of PD and seg height, there remains important and often unaddressed questions if our eyes’ binocular functionality, efficiency and comfort is being best addressed. It’s almost like the battle between optics and cosmetics has degenerated into a tribal affair, with the dilemma of frame choice dividing opticians into two camps: One favoring optical excellence and the other willing to do whatever’s necessary to obtain a cosmetically acceptable result. Like the Hatfields and McCoys, we hope that these warring sides will forget why they are fighting in the first place and begin to work together to deliver the best combination of both fine optics and pleasing cosmetics.

OPTICS: AS CLEAR AS DAY

Starting in the early 1800s, empirical experiments by early lens researchers like William Wollaston pointed out that the use of steeper lens curves expanded and increased the field of clear vision of even the smaller eyeglass lenses of the day. By mid-century, the new science of photography sparked interest in developing landscape lenses producing sharp wide angle images. At the same time glass science was evolving, optical pioneers such as Ernest Abbe, Carl Zeiss and Otto Schott were writing standards that defined the characteristics of scientific quality glass and its manufacture. By the early 1900s, researchers Ostwalt, Tscherning and Von Rohr began to employ mathematics and ray tracing in lens design, thereby codifying the science behind high quality precision ophthalmic lenses. By the 1920s, the early work of Ostwalt had been expanded upon and tailored for the mass production of corrective curve lenses by Rayton, Tillyer and Glancy. And with the invention of the first anti-reflection coating by Carl Zeiss in the early 1930s, the future of high quality prescription eyeglass lenses never looked brighter or sharper.

COSMETICS: DOROTHY’S DASTARDLY DEED

At the same time, frame styling began to explore new shapes and materials, moving away from tortoiseshell and horn toward the shine of specular gold-filled metals. Old style symmetrical shapes that were associated with eyeglasses’ medical origins, such as oval, round and hexagon began to fade, while new styles that mimicked the face’s naturally expressive features, such as eyebrows, appeared in frames that featured top line brow bars.

By the 1940s, American Optical, Bausch & Lomb, Art Craft and others introduced new and trendy asymmetrical shapes, and the notion of eyewear as a fashion accessory was born. But as this movement began to blossom, writer and poet Dorothy Parker coined a phrase of nine simple words—what we might call today a “meme”—that effectively characterized prescription eyewear owners as unfortunate souls: “Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses.” Eyewear, with its promise of clear sight, instantly turned into a medical pariah. Glasses returned to being reviled, and the public saw those who wore them with a negative color. Taunts such as “four eyes” stuck like glue to a child unfortunate enough to need them, scarring them against wearing glasses at all costs. Eyeglasses, arguably one of the most important yet intimate pieces of human apparel, became a marker for human deficiency. In social encounters, eyes would likely scan for tell tales revealing the strength of the Rx, including lens thickness, curves and reflections. Overall, the more obvious eye-face distortion became, the greater the social stigma associated with wearing glasses. The central challenge that still faces opticians to this day was laid down: Can you make a pair of prescription eyeglasses not look like a prescription pair of eyeglasses?

THE DILEMMA OF FRAME FIRST

Notwithstanding Ms. Parker’s acerbic observation, in the 1950s and 1960s, interest in new, larger and more unusual “fashion” lens shapes and frames began to grow on both sides of the optical isle. Retail opticians began tackling how to deal with the increased and more exposed lens thickness these asymmetric styles created in the lab. With few material choices available—crown glass being the choice of the day—guiding a prospective buyer with their stronger Rx in hand absolutely mandated that frame shape, size and fit be carefully considered via consultation with a trained optical professional. And so the dilemma of frame first was revealed: While optician and wearer are innately drawn to new and novel styling, both sides face hearing the other say “no” to their first frame choice, a place where the heart’s fondest want and desire lies. This “frame first” mentality continues to dominate all levels of the dispensing encounter, even to this day. The problem is that frame first often means one thing in the optician’s mind and quite another in the buyer’s.

THE WAR’S FRONT LINE: FLATTER VS. STEEPER

The result of the research and development done in ophthalmic lens design in its first century of development between 1800 to 1900 was the recognition that only steeper curved lenses delivered the widest and sharpest fields of view. But these steeply curved lenses came with a steep price: Additional thickness, bulging cosmetics and increased weight, all of which were no trivial consideration in the golden age of glass lenses. One of the ways flatter curves could be achieved without optical sacrifice was through the use of aspheric surfaces. But production technology available throughout the 20th century never matured enough to allow aspheric glass surfaces to be sold at an attractive price. It wasn’t until hard resin, polycarbonate and other higher index lenses became available that the aspheric designs and the flatter curves they allowed became commonplace. Once they did, however, a new problem surfaced: These lenses weren’t broadly available in all designs and photochromic treatments. So opticians and labs did what opticians and labs always do—they bent the rules of good optics by putting prescriptions on flatter spherical curves. The result? Fashionable cosmetics, albeit with poor peripheral optics. Only the makers of progressive lenses stayed true to their recommended but steeper base curves. Why? Because the only lens design that really can’t afford to start off with poor peripheral optics is a progressive lens design.

FREEFORM CONSEQUENCES

It was not until the early to mid-2000s, when true freeform lenses entered the marketplace, that flatter curves with acceptable peripheral optics, good cosmetics and thin profiles became possible. Everyone cheered “hurrah!” except the frame companies. They had to retool their frame bevel curves to become flatter. Originally 6-base bevel curves flattened to 4-base and 3-base. Today, we often see 0 base or flat bevel curves. While these surfaces are far less expensive to mill and form compared to steeper curves, they also make it tougher to glaze to an acceptable cosmetic standard, since few lenses with good optics are plano base.

OPTICAL CONFUSION

Today, choosing a new progressive design, even one with user reports that indicate favorable wearer acceptance or even outright enthusiasm, can mean having to deal with both cosmetic and altered perspective issues as the wearer transitions from the curves used by one design to a different lens and vice versa. In these situations, it can be hard to understand why lenses that represent differing design philosophies, such as Younger Camber and Varilux X—which represent the steeper curve versus flatter curve debate in the progressive zone—can both receive such glowing wearer satisfaction reports.

WINNING THE WAR

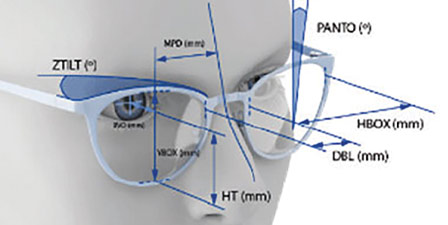

Whether you are faced with putting flatter lenses into steeper frames, steeper lenses into a flatter frame, dealing with unusually high or low pupil heights, extra narrow or wide PDs or even compound prism, opticians should never forget the rules of engagement when handling the adversarial parties at war in a pair of eyeglasses:

Know Your Base Curves—For finished stock and surfaced lenses, you should be comfortably familiar with vendor base curves for the Rx and material index you are addressing. Particularly in single vision, vendors may offer both spherical and aspheric designs, with different suppliers of the same lens type using different base curves for the same material. Remember that lens companies may have likely chosen sides in the war—favoring either steeper curves for better optics or flatter ones for superior cosmetics—resulting in less choice within their range than you thought. Mastering this is one of the first skirmishes you’ll face in the daily war.

Always Strive to Use the Highest Abbe Value Material Suitable to the Job—Higher Abbe materials generally follow lower indices of refraction, so a working knowledge of how a particular Rx will look like when finished is invaluable. Therefore, instead of your practice running away from in-office edging, run toward installing a state-of-the-art finishing lab. The money saved, convenience possible and lessons learned while glazing frames is what separates the opticians of the future from the ones now increasingly without jobs in the past.

Find Frames That Accomplish Job #1—And job #1 is knowing what frame styles your clients want that will fit, look great, be seen as good value while not posing unnecessary challenges for more difficult prescriptions. In other words, you must carefully curate every frame you carry.

Consider Freeform Your Friend—No other lens technology can offer you the degree of curve, index, Abbe and design choices as the universe of freeform lenses. They may cost more, but when other opticals say no, you can, should and will be saying yes.

Place Your Bevel Carefully—Today’s edgers, especially in skilled hands, can literally work miracles when placing a lens in the most optimal position within the frame. Often lens materials that have better optics but greater thickness can be used while never revealing a telltale that a thicker choice has been made. My first optical lab instructor, Professor John Williams, said it best more than 45 years ago: “There ain’t nothing better than beveling a nice, thick lens.” Some say it’s just technique. I say—in the hands of a master—it’s indistinguishable from magic.

Choose and Use AR Wisely—Considering the depth and variety of anti-reflection coatings available today, you should never be at a loss in choosing one that can help bend that ornery Rx into cosmetic submission. If you are committed to AR, remember that an AR coating that’s tough to keep clean can be inferior to no AR at all.

CEASEFIRE!

It’s easy to be tribal and take sides: You are either committed to optical excellence or only out for the best-looking cosmetics. But the reality is that the best recipe for any pair of glasses is far more complicated than this simple divide. It takes time, thought, reflection, experience, instinct, expertise and a touch of guts to create a truly spectacular pair of prescription eyeglasses. When the recipe behind a pair of specs is truly done well, the sum is far greater than the ingredients used or “cooking” methods applied. The return for your investment of time, thought and materials is hearing happy patients exclaim, “I wouldn’t think of going anywhere else.”

So instead of thinking of optics as in continuous war with cosmetics, try approaching it with a touch of zen: Find the rhythm and groove for every pair and go with it. Remember: While all the online and direct to consumer suppliers keep trying to simplify choices to remain efficient and profitable, you don’t have to. You have the luxury of achieving the most perfect balance of optics and cosmetics in every pair you make. Although it is a complex dance, it is also a rewarding opportunity—perhaps the best one in which to differentiate yourself from the competition. Don’t waste it.

TAKING IT TO EXTREMES

Somewhere in the outer fringes of the everyday optical world are the optical outliers, the specialty labs and opticians who take on the more difficult jobs that no one else is either equipped for or is willing to do. This is because labs of every type, as they become more and more automated in order to deliver higher quality and quantity of lenses, achieve these efficiencies by reducing job variables. These include the following:

- Reducing the Rx Power Range—In order to improve efficiencies, labs will limit the range of prescription powers they’ll make.

- Reducing the Lens Designs Offered—By limiting the amount of designs offered, labs reduce confusion and order entry errors.

- Reducing the Type of Jobs Processed—This is expressed in many ways: Some labs do exclusively glass. Others do only rimless and so on.

THE SPECIALISTS

What’s been your greatest eyewear challenge? The +20.00? The -40.00? The 9.00D cylinder? The plano-base Rx shield? The didynium Rx glass job? A difficult slab off on an executive bifocal? All these and more are tackled by a small minority of labs who specialize in doing the jobs that other labs refuse or can’t do. Some of these labs have access to specialized tools and techniques. Others have never tried to be anything other than a specialty lab. Still others are true renegades, being willing to bend or break every rule in the book in order to accomplish their mission statement: Complete customer wish fulfillment. Biconcave? Yes. Biconvex? Certainly. Saddleback? No problem. Rx shield? Can do. Satin and polished multifaceted custom tint-matched rimless? Ready!

The following is by no means an all-inclusive list, but these labs are ones I have found to have a proven track record of being willing to do what others are not, as long as you and your customer have the time and money ready to spend:

- Luxe Laboratory; Anaheim, Calif.

- Bad Ass Optical; Oakland, Calif.

- Aura Visual Concepts; Sauk Rapids, Minn.

- Drill Specialties; Massapequa, N.Y.

- Digital EyeLab; Hawthorne, N.Y.

- Quest Labs; Largo, Fla.

- Luzerne Optical; Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

- FEA Lab; Morton, Pa.

- Vision Craft Lab; Walled Lake, Mich.

AND ONE LAB TO RULE THEM ALL

And then there are the jobs whose difficulty surpasses even the specialists listed above. Where would you turn today for a -108D or a +70D job if one landed on your doorstep today? How about the Essilor Special Lens

laboratory?

This unique facility, known as “SL” for short, is located in Ligny-en-Barrois, France. Essilor has staffed it with a dedicated team of technicians and craftspeople led by Michael Kirkley who draw on 150 years of lens making experience to take on the toughest challenges in the ophthalmic lens arena. For example, a professional photographer, Jan Miskovic of Slovakia, had a prescription not commonly crossing the desk of a typical optician: -108.00D sphere combined with a -6.00D cylinder. Where else would you go to have this made? The team at the Essilor Special Lens Laboratory took on this challenging Rx with relish.

When a recent special request from Essilor Australia arrived, the skilled SL lab team took up the challenge of making a +70.00 diopter lens for Meg Zartorski, who suffers from Stargardt disease. Using two lenses and a polymer glue, the team successfully made this special lens, which is more than 30 percent stronger than any plus power attempted for ophthalmic use. The Essilor SL lab has also created an ophthalmic prism lens of 35 diopters! The SL lab is special indeed.

To learn more about the Essilor SL lab and watch a video about how they made Jan Miskovic’s lenses, read the Artist of the Lens feature in the March 2015 issue of 20/20.

–BS

TO BV OR NOT TO BV: THE FORGOTTEN ‘OTHER’ EYE

Perhaps with the sole exception of the slab off, that ancient technique of reducing prismatic imbalance at near originally conceived for segmented multifocals, most opticians spend little time thinking about all the binocular vision, aka BV considerations—such as retinal image size, dynamic or static magnification differences or unwanted positive or negative vergence demands—in the prescriptions placed before them on a daily basis. Why is that? The reasons are manifold:

The inherent neural plasticity and adaptation of the eye and visual cortex to adjust to unorthodox optical situations with antimetropic and anisometropic is well known. What is not well known or regularly quantified is the burden differing Rx powers, frame wraps and gaze angles puts on the brain and visual system. This results in increased strain, diminished comfort and visual utility, all things clearly important in today’s computer, phone, tablet and leisure-activity driven world.

Eyecare professionals find comfort in their anecdotal work experience, attributing a lack of observed or articulated complaint in these areas as clear evidence that people’s eyes will simply adapt and “get used to” the optical hand they’ve been dealt.

When any type of multifocal turns out to not work comfortably, the standard response is “you’ll need multiple pairs of single vision glasses.” Although this approach can appear to be the best solution on the surface, it really only superficially addresses the symptoms and not the underlying problems of differing static and dynamic magnification or unwanted positive or negative vergence demands inherent in these prescriptions.

The common wisdom has always been “not everyone can wear progressives comfortably.”

Fortunately, some companies have entered the marketplace with new analysis and optimization programs, along with companion freeform lenses, all of which are designed to prioritize binocular vision concerns that are regularly left overlooked for lack of awareness or ability to effectively measure and/or address. Both the Shaw Lens, invented by Dr. Peter Shaw, along with the Neurolens of SightSync, Inc., feature new diagnostic, measurement and lens fulfillment capabilities that can address even threshold BV problems central to many wearer’s eyeglass comfort. While the power of digital freeform lenses is essential here—the most important takeaway for ECPs is the need to become aware that solutions exist now for problems that both your patient and you have rarely thought or spoken about. Even meridional differences in magnification and prism due to changes in oblique cylindrical prescriptions can potentially be addressed with new binocular vision technologies. But be aware that lens base curves, bevel placements and lens thicknesses are being juggled in an unconventional manner to help optimize BV performance. The key outcome is how people who discover the pleasure of eyes that no longer fight each other rarely care as much about how the glasses look.

Today, it is no longer sufficient to prioritize just acuity and utility. It’s about high time that binocular beings enjoyed truly comfortable binocular vision. We have two eyes. We should always use both wisely.

–BS

Contributing editor Barry Santini is a New York State licensed optician based in Seaford, N.Y.