Photography by Bleacher + Everard

BY BARRY SANTINI

PART TWO OF A TWO-PART SERIES

Read Part One of “The New 20/Happy” »

As we’ve seen in Part One of this article, vision therapy remains an important but often underutilized treatment for handling all sorts of binocular vision disorders. However, another approach that is broader reaching and more impactful would be for opticians—the ones actually writing the orders for the glasses—to better understand how their daily lens and frame design choices might more favorably complement the binocular comfort of the wearer. Let’s take a closer look at that approach.

–Andrew Karp

MAINTAINING GOOD

BINOCULARITY WHILE BALANCING OPTICS AND COSMETICS

Ever since the introduction of the first blended/no line bifocal, opticians have had to deal with the growing importance of lens cosmetics, which is the extent to which a pair of prescription glasses can be made to look nonprescription. That blended lens, along with the first commercial progressives, were marketed primarily with the cosmetic advantage of “no lines.” But then as now, lines remain a telltale sign of age and deficiency.

Looking back, we can point to the era from the late 1950s to the early 1960s as the point where eyewear fitted and dispensed with purity of optics as the end goal began to change. From the 1970s forward, the importance of choosing a trendy, fashionable frame began to hold at least equal weight with any optical consideration. And by the 1980s, as eyeglass fashion exploded with super large eye sizes, we fully entered the era when opticians were engaged in the war between optics and cosmetics on a daily basis, a struggle that continues to this day. “Thinner, flatter, cheaper” remains the guiding mantra for most optical sales. The problem here is that prioritizing eyewear cosmetics almost universally works against delivering the best optics. Even if a trendy frame choice is not impacting optics, placing lens cosmetics as a priority will often negatively impact optimal binocular vision.

Today, at a time when frame brands and vision insurance often influence a patient’s choice of eyewear, what’s a conscientious, optics-focused dispenser to do? They must keep in mind that their first responsibility in filling a prescription is and always has been to design and fit eyewear that does no harm.

THE PERFECT OPTICS FOR

OPTIMAL BINOCULAR VISION: SMALLER, STEEPER AND THICKER

Designing glasses for optimal binocular vision starts by focusing on the optics and not being swayed by fashion considerations. Let’s review the thought processes that maximize optimal binocularity, especially when dealing with disparate prescriptions:

- Smaller eye sizes: Smaller frames help keep the eye’s gaze from straying too far from the optical center or prism reference point. This helps to reduce the amount of varying prismatic imbalance and differing image sizes seen by both eyes.

- Steeper curved lenses: Steeper curves can help in equalizing retinal image size by reducing vertex distance changes during peripheral gaze. A consistent vertex distance for all gaze angles also helps to reduce differences in dynamic prism and dynamic magnification, which originate from the greater peripheral obliquity that accompanies the use of flatter base curves. There are reasons why steeper curved lenses have been called “best form.”

- Thicker lenses: The choice to use thicker lenses, along with the use of steeper curves, is an important tool for equalizing retinal image sizes in disparate Rxs.

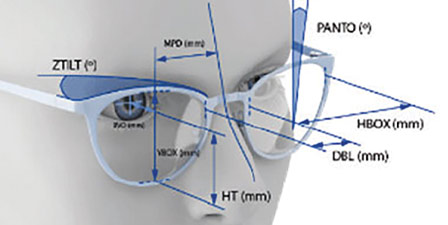

- Position of optimal wear: A frame that can be fitted with at least an 8 to 10 degree pantoscopic tilt, a wrap angle not exceeding 4 to 5 degrees and a close vertex distance will provide the least impact to binocular vision possible. Fitting this way ensures a consistent vertex distance, a reduction of oblique peripheral angles and the shortest distance away from the optical center/PRP for almost all gaze angles.

- Select a frame style from the iconic era: A frame shape chosen from the iconic style era—the 1930s to the 1940s—will not only help place the optical center at or near the pupil, but in concert with all of the above factors, help to create a solid foundation for the best binocular vision experience possible. Wearing the iconic styling of these smaller symmetrical and genderless shapes has always had a timeless appeal, enduring fashion quality and an important place in anyone’s eyeglass wardrobe.

THE CONSEQUENCES

OF POOR FRAME CHOICE

Fitting an unnecessarily large frame with a large vertical B dimension, worn down the wearer’s nose, with little pantoscopic tilt, a frame wrap of 8 degrees or more, and an optical center placed 8 mm or more below the eye’s pupil is the perfect recipe for a poor optical experience, let alone one meant to ensure optimal binocular comfort. So why do consumers tolerate such ill-fitting glasses? Because they want to, and they can—at least until that wearer starts showing signs of fatigue, headache, asthenopia or worse—suppression of the vision of one eye. Fitting eyewear as in the above example is the antithesis of the command for opticians to do no harm. Eyewear made this way, even with a mildly anisometropic Rx, can result in the misjudgment of distances while driving or walking down a set of stairs. Maybe there’s a reason behind why hospital ERs are seeing more seniors suffering falls while wearing multi-focal glasses.

SHORTEN THAT CORRIDOR!

In maximizing binocularity in progressive lenses, all ECPs should no longer rely on older maxims regarding trade-offs in progressive lenses using legacy surface molded designs. For example, the latest free form designs allow the routine fitting of far shorter corridors than was commonplace a generation ago without the penalty of increased astigmatism that would dramatically lower a wearer’s quality of vision. Shorter corridors allow for reduced eye rotation away from the lens’ prism reference point, which can help alleviate many imbalance issues. And every ECP should question the need for prism thinning in their progressive lens fitting. Cosmetic-prioritized prism thinning can and will aggravate binocular issues in disparate prescriptions.

THE DILEMMA OF 20/HAPPY

The day-to-day grind of most optical offices revolves around getting patients in and scheduled to see the doctor. This is followed by a visit to the office’s dispensary and the fitting of new lenses or glasses. Between these daily new fittings, adjustments and repairs, there’s the occasional patient with a visual problem patient that presents itself to the dispensing optician. Most of the visual problems seen at the dispensing desk revolve around progressive lens comfort or general comfort issues with both single vision and multifocal/progressive glasses. Given how many thousands of glasses are dispensed every day, it is surprising there aren’t more issues being seen and heard. Ask any decent optician in a good office about what makes a good pair of glasses, and they will state that proper lens design, placement and material choice are essentials. Yet, can it be true that the overwhelming majority of glasses dispensed are truly perfect or perfectly suited for any individual patient? If we’re being honest, the answer is not really. For as long as a mark of success remains an absence of complaint, we really don’t know whether the glasses are truly perfect or simply adequate. And 20/Happy is a metric that is wholly based on one thing: freedom from complaint.

Therefore, 20/Happy will always remain a dilemma. It can describe both what’s acceptable and tolerable, as well as what’s optimal. That it can encompass a wide variety of outcomes is no doubt why 20/Happy has become the favorite metric for ECP and consumer when describing satisfaction about human vision.

VISION REMAINS

ELASTIC AND FLUID

The main reason behind the “happy” in 20/Happy is that vision is both elastic and fluid: Elastic in its ability to adapt to a changing visual environment, and fluid as vision rarely remains stable or unchanging. From cornea to cortex, the inherent neuroplasticity of the entire visual sensory path has evolved to be flexible enough to adapt to almost any environmental challenge encountered. At the same time, human vision itself remains fluid and changing. On a daily basis, it is influenced by many things, from your morning sugar intake to the at-the-moment integrity of the precorneal tear film.

The presence of these two characteristics, elasticity and fluidity, works against clearly describing any individual’s visual state in clear and absolute terms. For example, there has always been a lot of inherent gray surrounding both the final numbers prescribed on exam day and how long an adaptation will be required after the eyewear is dispensed. And although ECPs cannot fully eliminate the uncertainty of how optimal our visual efforts are, we can certainly act to reduce it.

LIFELONG LEARNING

Just a few generations ago, the whole idea of taking a monocular PD or measuring the pantoscopic tilt was not part of the daily life of most eyecare professionals. Therefore, just because you’ve been practicing for years does not mean that you know everything, or that everything you know is all that matters. As for 20/Happy’s role as a reliable outcome-based metric, the good news is found in its inherently forgiving nature. For example, most ECPs’ well-intentioned Rx or eyeglass treatment plan will more likely than not prove “satisfactory.” But also because of this, 20/Happy can also lull ECPs away from engaging in an earnest journey to uncover what’s truly best, especially if initial complaints of discomfort can be conveniently dismissed with a simple “Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it.” Paradoxically, 20/Happy can be seen as both a reality check and a lazy man’s cop-out. How it is applied will be defined by your depth

of knowledge.

STRIVING FOR

20/HAPPY BINOCULARITY

These are confusing times for the eyeglass consumer because the optical industry appears to be always sending out mixed messages. We trumpet about the value of novel, more advanced and expensive spectacle solutions for problems consumers didn’t know they had in the first place. At the same time, the online channel is growing fast, offering easy access to robust product information and less expensive over-the- counter solutions. How could any eyeglass consumer properly parse the real value of all these choices for themselves? That’s where today’s eyecare professional enters the picture. By remaining open and proactive to discovering the latest information about new technologies and product solutions, your value is assured as your community’s local eyecare expert.

Today, doctors should be seeking out opportunities to integrate new technologies that promise to better serve their patients and expand their scope of practice. And although opticians cannot directly participate in diagnostics or assessment, they should embrace their gatekeeper role as the most convenient point of contact for all who seek information personalized for their eyes. Most importantly and particularly with disparate Rxs, opticians should remember that their first responsibility is to not interfere with the binocular function of the wearer. In some ways, this responsibility might be akin to the “Duty to Warn” regarding impact resistance—because all patients deserve the opportunity to be advised on the best optical solutions available, and not just the low hanging fruit of the adequate, cosmetically pleasing or the least expensive. This will require most dispensers to perform a wholesale shift in their daily work approach, perhaps away from a patient-driven frame and lens selection, and toward one guided by the expert optician’s recommendations regarding optimal binocular function. To adhere to the optician’s do-no-harm maxim, a dispenser should continually aspire to perform their job at the highest possible level. Pursuing the best 20/Happy means asking oneself: “Am I optician—or cosmetician?”

‘Freedom from Spectacle Dependence:’ A Confusing Message For Binocular Comfort

Most eyecare consumers, if asked whether their ECP is primarily focused on optimizing their binocular vision, would reply “no.” More likely, they would say that their ECP helps them see sharply and makes them look good in glasses.

This is not an optimal situation, because there is so much gained through a fuller and more holistic approach to good vision—one that sees vision excellence as going beyond just good acuity and fashionable frames. So why don’t eyewear consumers pursue solutions that get their two eyes working on the same team? I see three reasons: First, human vision has evolved to be both elastic and adaptive—always ready to adjust to keep the flow of information unimpeded to our brain. Yet because of vision’s inherently compensatory nature, people can often be only vaguely aware when a deficiency in binocularity is present. And unlike our sense of temperature or thirst—where an obvious action can provide immediate relief—the corrections needed to improve binocular comfort are neither obvious nor easy to access. Maybe this is a reason why consumers don’t even realize when they’re experiencing a vision coup—meaning one of their eyes is increasingly taking over for the other.

The second reason for consumers’ lack of awareness about binocularity is the confusing message that all levels of ECPs—from optician to ophthalmologist—continue to promote by recommending correction modalities that inherently compromise binocular vision. Starting with the seemingly innocent recommendation of over-the-counter (OTC) reading glasses, or “cheaters,” and continuing with the fitting of monovision contact lenses, the message being sent out is that you can avoid needing “real” glasses. This confusing message extends all the way to monocular-prioritized refractive surgery, either via laser or implanted lens. Surgical modalities are indeed permanent, but also often fail to fully deliver on the promise of “freedom from spectacle dependence.” In an age where demonstrating one’s personal sense of style has never been greater, why is it that wearing eyeglasses is still treated by even eyecare professionals as common sense that glasses should be avoided at all costs?

The challenge for all ECPs is twofold: As long as spectacles are cast as an answer for a deficiency and not as a solution for optimal vision, we can’t blame the public for not wanting glasses or for seeking the least expensive option that will get them to 20/Happy.

–BS

Contributing editor Barry Santini is a New York State licensed optician and contact lens fitter with Long Island Opticians in Seaford, N.Y.