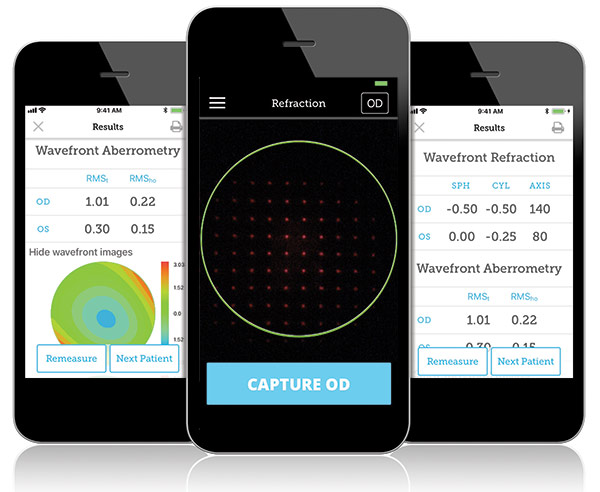

Smartphone screen images courtesy of Smart Vision Labs

By Barry Santini

No aspect of Main Street Optical has been arguably more impacted than from ongoing advancements in optical technology. Beginning almost 50 years ago with the arrival of Essel’s Centramatic, the world’s first advanced pupil measuring machine, through the Briot model 5000, the world’s first patternless edger, all the way to the latest smartphone-based refracting devices, eyecare professionals find themselves conflicted about the newest technology. Although many initially resist the changes that result from new technology, some eventually embrace advancements that could pose a threat to their very existence.

ECPs are seeing this no more clearly today than in the combination of online eyewear, smartphone refraction and advancements in measurement technologies, all of which seem to want to make humans obsolete in a prescription eyewear transaction. And nothing promises to be more disruptive to optical than the rapid developments in smart refraction and telemedicine. In light of this, who can really blame an ECP for wondering, “Will I have a job in the optical landscape of the future?”

The short answer may surprise you: “Yes, more than ever!” And in that response there’s equal parts mixed in of good and bad news. First, the bad news: You’ll need to concede that many hard-won optical hard skills—let’s rename them “cold” skills—will be rendered obsolete or markedly diminished in importance by advancements in optical technology. The good news is that a new suite of “hot” skills—embracing both selling and interpersonal skills—will rise in importance and require hard work to master, develop and put into play. But by taking up the challenge of acquiring these skills along with a new way of thinking, you’ll become ideally prepared to embrace and leverage all the latest technologies needed to succeed in the tough and volatile optical landscape of tomorrow.

HOT AND COLD

In the first two-thirds of the 20th century, when optical was a “closed” system, old-style hard skills ruled—skills such as knowing how to make and measure spectacles, which could be learned on the job, skills which were once the absolute bedrock that professional opticianry was founded upon. And if you also “knew optics,” even if it was also learned on the job, so much the better.

But back then no one could have predicted how new science developed primarily from spinoffs in the space race would so dramatically accelerate the computational, communicational and cooperative technologies that eventually would impact traditional opticianry. With 20/20 hindsight, it should be obvious that the apprentice-journeyman-master knowledge path would inevitably be displaced from the spotlight of center stage and into the shadows of diminished importance. This is why the older, hard skills set of opticianry is best described as cold today. We can see this clearly in today’s job headlines looking for quality opticians. Almost all business owners will confide that years of experience has taught them to always look for the right personality type and train to fit. It’s easy to appreciate that personable and inviting sales-centered personalities now form the bedrock of any brick-and-mortar business. And in today’s ultra-competitive optical landscape, no one has time to waste training and integrating a new employee into the nuances of company culture, only to cut them loose if the bottom line is not improving. Owners therefore find resonance in the soundbite “Hire slow, fire fast.”

Today’s new “hot” skills encompass qualities such as appearance, personality, sensitivity, empathy, problem solving, readiness, efficiency and ultimately, a willingness to own, manage and care for your customer’s total optical experience. The easiest place to see an example of this in action is to walk into any Apple store, even if all you want to do is browse. You are immediately and warmly greeted with a smile at the door and quickly directed to where you should go or where to look for what you’re interested in. You may then be assigned to a handler, who will guide you, quickly assessing your needs and goals, retrieving products, explaining costs, financing and warranties, and using proprietary technology that eliminates the need for a traditional cashier. Your sale is quickly processed, products bagged and your receipt e-mailed to you. Voila! We can only hope that eyeglasses, which interestingly share about the same purchasing frequency as phones and computers, could one day be managed in as efficiently, friendly and satisfying a manner.

Maybe it can. It only takes a small change in your conversational habits to make it happen.

A CONVERSATION ABOUT NEW TECHNOLOGY

Traditionally, when an ECP initially encounters the arrival of a new optical technology, the process of getting acquainted usually begins in a form of a conversational denial, wherein the technology is profiled as an unwanted or unneeded intruder whose promise is pitted against the benefits of what’s tried and true. Next, the dialogue slowly evolves subconsciously to one that includes risk assessment, i.e., “Do the promised benefits outweigh the monetary risks or implementation challenges?” This is generally the point where the “early adopters” jump in because they, by definition, have both less fear of the new and novel, and are also more willing to entertain risk based on the novelty rather than the reality of what the tech will deliver. Often the voice of the “tire kicker” will also enter the conversation about now. Using metrics based on personal experience, the tire-kickers engage in a type of devil’s advocate role play to assess if the tech’s promise is fundamentally sound. The problem with using past experience is that it is old while the technology is new. The danger here lies in applying a wrong or inappropriate metric, and instead of embracing the new tech, ECPs summarily dismiss its value. For example, when evaluating a prospective digital centration device, your PD is taken. If that value doesn’t compare favorably with the optician’s own/known PD, they lose interest in the device. It’s a classic case of “throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

OLD DOGS AND NEW TRICKS

Measuring PDs and pupil heights has come a long way from the days of your grandfather’s PD ruler. Up until the early 1960s, most took PDs by measuring across from pupil to pupil and recording the found binocular value. For large segment multifocals and single vision lenses, there were no significant complaints of reduced reading utility or unwanted prism when using binocular PDs. Monocular PDs, on the other hand, only became recommended with the introduction of the first commercially produced progressive, the original Varilux (1) by Bernard Maitenaz, in his work for Essel of France. What Essel found was that the smaller intermediate and reading zones of the Varilux lens were far more sensitive to errors in misalignment from inaccurate binocular PDs, resulting in a reduction of reading utility that, for many, made this groundbreaking progressive lens unusable. Their solution became to emphasize taking monocular PDs, as these values promised to more appropriately align the power umbilic of the progressive. But teaching the opticians of Europe to change their treasured way of measuring PDs was met with extensive pushback, i.e., the opticians “saw nothing wrong” with their ruler and binocular PDs. Besides, they offered: “No one really complains about spectacles made using my binocular measurement.”

Yet Essel remained adamant: Opticians, they felt, must learn to take accurate monocular PDs for all types of lenses and not just progressives. To this end Varilux prioritized the concept of using the corneal reflection, or reflex, in measuring pupillary distances. Their research showed that the corneal reflex was a much more accurate measure of where the human eye is looking, i.e., the visual axis is pointing. The main objection raised was in reaction to the binocular value of corneal reflection PDs was routinely 1 mm to 2 mm smaller than the typical ruler measured PD. But even in view of this, the vast resources of Essel was thrown behind promoting the corneal reflection way of measuring and in the early 1970s, Varilux recommended opticians use only the new Centromatic photo taker or the new corneal reflex pupillometer to secure the most satisfied patients when fitting Varilux progressive lenses. Imagine the shock, however, of being asked to part with $200 for the pupilometer to as much as $2,500—plus the cost of Polaroid film—for the larger and more impressive Centromatic. Compared to the average $0.50 cost of a lowly PD ruler of the time, opticians saw no reason to risk large amounts of money for a new technology designed primarily for a lens whose optics, utility, distortion and unwanted prism were entirely abhorrent to the sensibilities and high standards of their training. Further, the voice of the tire kicker now entered the discussion, strongly persuading these seasoned craftsman that this new technology cannot be of any real worth as its binocular PD value was clearly wrong, i.e., they threw the baby out with the bathwater.

Today, you’d be hard pressed to find an ECP who wouldn’t agree that the taking of accurate monocular PDs is amongst the most important hallmarks of a quality, skilled optician.

Remember this story, you old dogs, the next time new tech comes knocking at your door. It just may be time to learn a new trick or two.

THE CHALLENGE OF SMART REFRACTION

Now that the PD wars are receding behind us, the next new technology that appears to pose a threat to ECPs is smart refraction. Going beyond the early auto-refractors, today’s smartphone-based auto-refractors are promising ECPs far less time to obtain accurate prescription numbers, while substantially improving both patient and ECP confidence in the same. Patients have long disliked the dilemma of having to choose between “Which is better, number 1 or number 2?” especially as they are rarely coached in advance that the endpoint of the testing is when both choices look the same. The anxiety and loss of confidence on the part of the patient is palpable and should never be trivialized. And as much as the traditional subjective refraction is held up as a gold standard, an expertly arrived at Rx, by itself, is still not a confident predictor of patient success and satisfaction with their completed eyewear. No, the exact recipe for cooking that goose remains as elusive as the pursuit of the ideal progressive design.

Nevertheless, the technologies of smart refraction are forging ahead at a frenetic pace today. Advances in wavefront analysis, point spread function, RMS metrics and high order aberration analysis are all beginning to help us amass, assess and understand what makes up the perfect eyeglass prescription. And now, advancements in smart refraction are helping to fuel improvements and acceptance of telerefraction and telemedicine. Although ECPs may see this as a threat to their normal way of doing business, the expansion of exam availability and convenience will only serve to increase the total number of exams performed and not reduce your own. Remember: A rising tide floats all boats.

ALLY OR ADVERSARY

So what’s it going to take to make you embrace rather than repel new technologies? Sure, it’s depressing to admit that the attraction of mastering old style hard skills has cooled. But what’s exciting is the recognition that a new, hot set of interpersonal skills can allow Main Street Optical to finally connect to their patients in the fundamentally intimate way that only eyewear, the most intimate of personal accessories, can. This week, why not start training your staff on the importance of combining both hot and cold skill sets to arrive at a new breed of confident, inviting and warm optician, one to whom patients willingly give their trust and follow their purchasing advice.

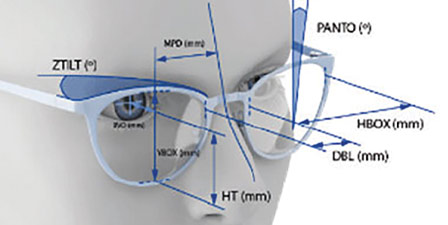

Or perhaps try revisiting some new and advanced technologies that you may have recently dismissed as unnecessary or too expensive. There’s lots of new tech available to measure PD, height, pantoscopic tilt, vertex and wrap. And if you don’t have an in-office finishing lab at present, you’ll find the current offerings far more affordable, sophisticated and easy to use than ever before. Are you courageous enough to recognize the future and actively pursue the latest smart refraction technologies?

Most of all, it’s time to make a fundamental change in your optical attitude. Don’t wait, as our fathers did, for “color TV to be perfected.” Try embracing new technology as an ally rather than an adversary. It’s an exciting time to be in optical… yea or nay? ■

WHAT’S IN A PD?

In offices around the country, expensive digital centration devices, or DCDs, can be found unused, languishing in a corner and covered with a tarp or layered with dust from lack of use. Why? Because the personnel in the office lost confidence in the measurements being obtained. Often this can be traced to operator error. Other times it simply reveals a lack of training and or understanding on how to fully and correctly use them. Again, metrics such as comparing simple monocular PD and height values with those taken by hand eventually ended up negatively impacting trust and elevating the perceived risks of using said measurements. I have found that if the operators would have been willing to invest the necessary time, they would’ve seen that perhaps their confidence in their treasured manual way of measuring might just need re-evaluation. One of the most extensive studies of three different pupillary measuring modalities was done in 2010 by Dr. Wolfgang Wesemann of the School of Optometry in Cologne, Germany. Although the study also included measuring position of wear (POW) values, the conclusions reveal, with a 95 percent confidence value, the accuracy of each binocular PD measuring modality:

Ruler: Within 1.54 mm

Pupillometer: Within 0.74 mm

Digital Centration Device: Within 0.36 mm

Please note that each subsequent modality is approximately twice as accurate as the previous, making the DCD four times more accurate than a PD stick! But opticians still push back: “Who cares about binocular PDs anyway? It’s monocular that really counts!”

They’d be wrong, and here’s why. Often left out of the discussion of PD metrics up until recently has been the issue of eye dominance. Follow this line of thought: A person’s dominant eye is also the brain’s sighting eye, and a progressive wearer will therefore naturally align the corridor for the dominant eye by adjusting lateral head position to do so. If the monocular PDs are accurate, you’ll have no residual error or problem. If the monocular PDs are off, the wearer may experience loss of reading utility resulting from the reduced overlap of the reading zones and in particular, the intermediate progressive corridor. But even if the monocular PDs are off, as long as the binocular PD is accurate, the progressive zones will properly align and a small but minor amount of head cape will bring the object of regard into proper focus with no loss in reading width utility for the wearer. But if the monocular PDs are off and the total binocular PD is off, the brain will align the corridor of the dominant eye, resulting in a compounding of the corridor alignment error for the companion eye. So it’s really an accurate binocular PD that matters most in successful progressive fitting. And no device delivers a more accurate and objective binocular PD value than a properly used digital centration device. Take that, tire kickers!

(Thanks to Tom Clark, OD, for his explanation behind the importance of binocular PDs and eye dominance in fitting progressive lenses.)

Contributing editor Barry Santini is a New York State licensed optician based in Seaford, N.Y.